INTRODUCTION

Natural gas and nuclear power plants are two types of electric generating resources in the United States (US) that consist of very different design features and sources of fuel to generate electricity. To understand their respective differences in capital costs, fuel type, operational costs, efficiency rates, environmental impacts and other factors that impact performance, viability, and public perception, we need to look at some comparisons.

NATURAL GAS POWER

The combined-cycle natural gas power plant employs a dual approach to generate electricity. The process begins with the gas turbine compressing air and blending it with natural gas, raising the mixture to a high temperature. This high-temperature air-fuel combination then flows through the turbine blades, inducing rapid rotation. The rapid rotation of the turbine propels a generator, transforming the rotational energy into electricity. Simultaneously, a heat recovery steam generator (HRSG) captures exhaust heat that would otherwise be lost through the exhaust stack. The HRSG utilizes this captured heat from the gas turbine to produce steam, redirecting it to a steam turbine. The steam turbine, in turn, transfers its energy to the generator’s drive shaft, where it is further converted into additional electricity. This integrated process optimizes the use of both the gas turbine and waste heat, maximizing the overall efficiency and electrical output of the combined-cycle natural gas power plant combining a gas turbine with the capture of waste heat from the turbine to enhance efficiency and electrical output.

NUCLEAR POWER

In contrast, a conventional nuclear light-water reactor (LWR) operates as a thermal device, utilizing ordinary water as its coolant. A nuclear plant relies on a solid form of fissile uranium, specifically enriched U-235, as its fuel and employs a neutron moderator to regulate the fission process. Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom divides into two or more smaller nuclei, releasing both energy and neutrons in the form of radiation and heat. The uranium oxide fuel used, primarily composed of the U-235 isotope, undergoes enrichment from its natural state of 0.72%, enriched to 5%-7% to sustain a chain reaction. Following enrichment, the fuel is fashioned into pellets, which are then sealed within metal tubes known as fuel rods or fuel assemblies. The water within the reactor serves dual purposes: it cools the fuel and moderates the neutrons produced during the fission of uranium atoms. Maintained under high pressure, as in a pressurized-water reactor (PWR), this prevents the water from boiling. The heat produced by the fission reactions is transferred from the water to a secondary circuit through a heat exchanger. Within this secondary circuit, water is allowed to boil, generating steam. The resulting steam propels a turbine, which, in turn, spins a generator to produce electricity. Notably, approximately two-thirds of operational nuclear reactor power plants in the US are PWRs.

ELECTRICAL POWER

According to the International System of Units (SI), power is the rate energy is transferred to complete some designated work. The joule is the basic unit of power, defined as the amount energy (i.e., force) needed to displace the mass of an object through a distance of one meter. The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is an international standards organization for electrical, electronic, and related technologies. The IEC defined the watt as a measure of a unit of power, where one watt is equivalent to one joule per second, therefore, the joule is equivalent to one watt-second.

The watt is named after James Watt, a Scottish engineer. James Watt did not directly develop the electrical unit of measurement for power that bears his name but was named to honor his contributions to the development of the steam engine during the Industrial Revolution. The decision to use the term “watt” for the unit of power in the electrical context was made by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) in 1889.

The following are various multiples of the watt used in different contexts:

Kilowatt (kW) = 1000 watts

Megawatt (MW) = 1,000,000 watts or 1000 kilowatts

Gigawatt (GW) = 1,000,000,000 watts or 1000 megawatts

Kilowatt-hour (kWh) = 1000 watt-hours

US annual per capita electricity consumption = 12,072 kWh/year

In December 2022 the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) published data stating the total utility-scale electricity-generation capacity from all power sources (i.e., natural gas, nuclear, coal, hydro, geothermal, solar and wind) in the US was 1,199,655 MW, with an average capacity factor of approximately 54.7%. This results in the generation of about 4,265,000 Gigawatt-hours (GWh) (a Gigawatt is equal to 1000 Megawatt-hours) of electricity annually. Hence, the annual per capita US electricity consumption is about 12,072 kWh/year. In comparison, for the 10 largest economies in the world, Canada’s has the largest annual per capita electricity consumption amounting to 13,863 kWh/year, China at 6,032 kWh/year represents about the average annual per capita electricity consumption, and India being the lowest at 1,208 kWh/year.

Notably, based on data above, the US retains about 45.3% of spare or unused electric installed capacity.

The “capacity factor”, mentioned above, signifies the ratio of what an electric plant can produce in Megawatt-hours (MWh) at maximum output (installed capacity) to its actual generation output over a given period. While not a measure of efficiency, it indicates how frequently a power plant operates at its full capacity. A higher capacity factor implies more electricity production relative to installed capacity, while a lower factor suggests less electricity production.

COMPARISONS – Natural Gas vs. Nuclear power (Table # 1)

In 2022, the EIA stated there were 1793 natural gas power plants operating in the US and 77 plants under construction. The installed capacity of the plants operating is approximately 509,554 Megawatts (MW) or 284 MW per plant (509,554 MW/1,793). On average, these plants operate at 54.4% of installed capacity (capacity factor) and provides 2,403,006 GWh of electricity, providing 40.3% of the US electricity demand.

In contrast, there are 93 nuclear power plants operating in the US and 2 plants under construction with an installed capacity of about 102,095 MW or about 1,098 MW per plant (102,095 MW/93). These power plants operate at an impressive 93.0% capacity factor (NRC 2020 data), however, only accounted for 818,766 GWh or 13.7% of the total US electric power consumption.

The remarkable 93% capacity factor for nuclear power plants is attributed to its design features (operational limitations) that prioritize safety, ensuring the reliability of the reactor core, fuel rod integrity, and dependable fuel cooling and control systems. These features enhance the use of installed capacity but necessitate continuous operations at nearly full capacity, 24/7, with shutdowns only for maintenance or refueling. The lower electric power generation of 13.7% is due to the lower number of power units versus natural gas plants.

In contrast, natural gas power plants, due to their greater operational flexibility, can swiftly respond to changes in power demand and hydrocarbon fuel type. However, this flexibility results in a lower capacity factor of 54.4%, solely determined by the demand for electricity within the US power grid.

This analysis underscores that nuclear power plants operate closer to full capacity due to their fuel safety design requirements compared to natural gas power plants that have greater fuel distribution entrée and near zero shut down and ramp up safety limitation. These features provide greater operational flexibility for natural gas plants resulting in the ability to operate at lower installed capacity, which is driven by electricity demand.

To compare the cost associated with generating one kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity from natural gas as opposed to nuclear power, the industry employs a widely recognized metric known as the “levelized cost of electricity” (LCOE). LCOE serves as a benchmark for evaluating costs and facilitating comparisons of other alternative energy production. For both natural gas and nuclear power plants, LCOE encompasses the average total expenses, including capital cost of construction and financing, operational and maintenance costs, fuel expenditures and transportation, and the anticipated electricity output throughout the determined lifespan of the plant. LCOE is typically denoted in dollars per megawatt-hour ($/MWh) or cents per kilowatt-hour (c/kWh). The EIA defines LCOE as the average revenue per unit of electricity ($/MWh) that would be required to recover the capital and operating cost of the power plant, during an assumed financial life.

The actual electricity generation from nuclear power is very inexpensive but incredibly inflexible. Once a nuclear power plant is running, it runs at the same rate regardless of demand, therefore producing energy that is either wasted, unless consumed or sold to another utility. On the other hand, natural gas plants can be expensive to operate depending on the price of natural gas, albeit very flexible versus nuclear plants having faster ramp up speeds and ability to stop and start generation based on fluctuating demand.

In the EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook 2022 (AEO2022), the LCOE for a typical combined-cycle natural gas plant versus a conventional light water reactor (LWR) in the US, expressed in 2022 dollars per megawatt-hour ($/MWh), amounted to $46.90 versus $95.10, respectively. Therefore, based on the EIA 2022 data, nuclear power has as a higher LCOE per $/MWh by a factor of 2 versus natural gas power.

The efficiency of an electric power generating plant is the ratio of the electric out put to the energy input. The higher the efficiency, the less energy is used in the process.

According to PCI Energy Solutions, a typical LWR nuclear power plant’s efficiency varies between 33% and 45%, which means that between 67% and 55% respectively of the energy produced by the nuclear fission reaction is lost as heat and radiation. In contrast, the combined-cycle natural gas plant uses natural gas to drive a turbine combined with a steam turbine designed to utilize waste heat from the gas turbine to generate additional electricity, providing 60% efficiency. Therefore, the natural gas plants are more efficient versus nuclear power plants by a factor of 2.

The capital cost of a nuclear power plant versus a natural gas plant Is complex having variable factors that depend on location, plant size, design, technology implemented, financing and most importantly, regulatory challenges. However, in 2019 the World Nuclear Association estimated the capital cost for a nuclear power plant at about $6,155 per kilowatt (KW) of installed capacity, compared to the capital cost of a natural gas plant at about $978 per kW of installed capacity. This means that a nuclear plant with a capacity of 1,000 megawatts (MW) would cost about $6.2 billion to build, while a natural gas plant with the same capacity would cost about $1 billion to build. Therefore, the natural gas plants have a considerably lower capital costs versus nuclear power by a factor of 6.

The permitting and construction time for a natural gas plant and nuclear power plant is complex and can be variable depending on plant intricacies and size. Based on a report by the US Government Accounting Office, a natural gas plant from pre-filing to certification is about 558 days. According to Power Engineering, a combined cycle natural gas plant typically takes about 2.5 years from study phase to delivery of equipment, although some projects have taken 4 to 5 years to complete.

For nuclear power plants, a US Nuclear Regulatory Commission report stated that under a combined license process, whereby both construction permit and operating license is combined into a single license, can take 10 to 12 years from the time the application is filed to the time a plant begins operations. Another report by Energy Understood, the construction time for a nuclear power plant can vary depending on size and complexity of the project but takes on average about 10 years to permit and build a large nuclear reactor. Further, according to the World Nuclear Industry Status Report, nuclear power plants take an average of 10 years to permit and build.

Therefore, based on the foregoing paragraphs, the permitting and construction time to build a natural gas plant is 4 times faster than nuclear power (2.5 years vs. 10 years).

Both nuclear and natural gas power use water for cooling purposes, which can affect the availability and quality of water resources. Nuclear power plants typically use more water than natural gas power plants, but the amount of water used depends on the type of cooling system used. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), nuclear power plants withdrew an average of 25.1 gallons of water per kWh of electricity generated in 2018, while natural gas power plants withdrew an average of 7.7 gallons of water per kWh. However, water withdrawal is not the same as water consumption, which is the amount of water that is not returned to the source after use. According to the EIA, nuclear power plants consumed an average of 0.5 gallons of water per kWh of electricity generated in 2018, while natural gas power plants consumed an average of 0.2 gallons of water per kWh.

Both nuclear and natural gas power require land for the construction and operation of power plants, as well as for the extraction and transportation of fuels. Nuclear power plants typically require more land than natural gas power plants, but the land use impacts depend on the location, size, and design of the power plants. According to a study by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), the median land use intensity of nuclear power plants in the United States is 1.12 acres per GWh of electricity generated per year, while the median land use intensity of natural gas power plants is 0.74 acres per GWh per year. However, these values do not include the land use impacts of fuel supply, which may vary depending on the source and quality of the fuels.

From an environmental perspective, nuclear power and natural gas power have very divergent public concerns. The public perception is that nuclear power has a major role to play in clean energy transmission having zero CO2 emissions. However, each individual world view is more emotionally centered around nuclear powers risks regarding its creation of radioactive waste, such as uranium mill tailings, spent reactor fuel and other unknown radioactive materials, all of which can remain dangerous to human health for thousands of years. These concerns also extend to less tangible personal values and beliefs, regarding trust in government authorities, industry, and the media coverage. On the other hand, although natural gas power is seen as a cleaner, more cost effective and efficient electric generating alternative and emits considerably less CO2 emissions than coal and petroleum, it still has a carbon footprint regarding the climate change debate. To understand these concerns better, the following are some facts and comparisons.

From an environmental perspective, specifically the CO2 emissions (i.e., air pollution), a natural gas plant exceeds that of a nuclear power plant. According to a report by the World Nuclear Association, the lifecycle CO2 emissions of natural gas power plants in the United States range from 410 to 650 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per gigawatt-hour (CO2e/GWh), while the lifecycle CO2 emissions of nuclear power plants range from 9 to 70 tonnes of CO2e/GWh. Averaging the results of the studies used in the report, the lifecycle emissions of natural gas power plants are about 25 times higher than the lifecycle emissions of nuclear power plants.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the direct CO2 emissions of natural gas power plants in the United States are about 117 pounds of CO2 per million British thermal units (MMBtu) of natural gas, while the direct CO2 emissions of nuclear power plants are zero. Assuming an average heat rate of 7,900 Btu per kilowatt-hour (kWh) for natural gas power plants and an average capacity factor of 90% for nuclear power plants, the direct emissions of natural gas power plants are about 413 grams of CO2 per kWh, while the direct emissions of nuclear power plants are zero.

To put the CO2 emissions of natural gas plants into perspective, several studies have been undertaken comparing CO2 emissions between natural gas power plants and other sources such as coal power plants, petroleum, and automobiles in the US. One method employed in these assessments is the calculation of grams of CO2 emitted per kilowatt-hour of usable energy produced (gCO2/kWh). This metric factors in the efficiency of the energy conversion process and the carbon intensity of the fuel source.

According to the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES), natural gas combustion yields approximately 500 gCO2/kWh, which is half the emissions of coal (1,000 gCO2/kWh) and one-third less emissions from petroleum (750 gCO2/kWh). The C2ES estimates that gasoline cars and trucks emit around 1,300 gCO2/kWh, more than double the emissions from natural gas power plants. However, this comparison doesn’t encompass emissions from fuel extraction, transportation, and processing, which can also vary and add significantly to CO2 emissions related to automobiles.

An alternative approach to comparing CO2 emissions from natural gas power plants and automobiles is to examine the total annual emissions from each sector. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the electric power sector emitted 1,614 million metric tons of CO2 in 2022, with 38% originating from natural gas. In the same year, the transportation sector emitted 1,507 million metric tons of CO2, with 82% attributable to gasoline and diesel. Consequently, natural gas power plants contributed about 613 million metric tons of CO2, while gasoline and diesel vehicles contributed around 1,235 million metric tons of CO2 in 2022.

These figures highlight that natural gas power plants, automobiles, coal power plants and petroleum contribute to CO2 emissions in the US. However, natural gas power plants in comparison have a much smaller carbon footprint per unit of energy.

Although nuclear power produces no “greenhouse” gas emissions (CO2), nuclear and natural gas power have indirect emissions from the operational lifecycle of the power plant, such as construction, fuel supply waste management (particularly with nuclear power) and decommissioning. According to the World Nuclear Association, nuclear power produces radioactive waste, such as uranium mill tailings and spent reactor fuel, which can remain radioactive and dangerous to human health for thousands of years.

The biggest on-going liability for nuclear power plants and the nuclear power industry in the US is spent fuel storage and disposal (i.e., high-level radioactive waste). The Department of Energy (DOE) office of Nuclear Energy (NE) is the US Government agency responsible for ongoing research and development (R&D) related to long-term disposition of spent nuclear fuel (SNF), representing high-level radioactive waste (HLW). Interim on-site storage is currently the most common practice for managing spent fuel worldwide, as most countries have not yet decided or implemented their long-term solutions.

The current practice for storing SNF from nuclear power plants in the US is to use a combination of wet and dry storage methods, depending on the availability and capacity of the facilities. Wet storage involves keeping the spent fuel in specially designed pools filled with water (i.e., spent fuel pools) which cool and shield the fuel from radiation emissions. Dry storage involves placing the spent fuel in sealed metal or concrete containers, which are then stored in independent spent fuel storage installations (ISFSIs) at or away from the reactor sites.

According to a report by the Congressional Research Service, there were 62,683 metric tons of commercial spent fuel accumulated in storage in the US as of the end of 2009. Of that total, 48,818 metric tons – or about 78 percent – were stored in spent fuel pools located on the reactor site. 13,856 metric tons – or about 22 percent – were stored in dry casks, on the reactor site. This total increases by 2,000 to 2,400 tons annually. Therefore, based on this data, from 2009 through 2023, over the last 14 years the nuclear power industry generated an additional 28,000 metric tons of spent fuel now totaling 90,683 metric tons of nuclear plant radioactive waste is in storage on the reactor site.

Another downside to the competitive viability of nuclear power is that the cost of spent fuel management and storage is not included in the total cost of producing a kWh of electricity. Historically, this cost has been indirectly passed on to the consumers through a fee that the nuclear utilities previously paid to the federal government based on the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982 (NWPA). NWPA established a national program for the disposal of spent fuel and high-level radioactive waste in a permanent geologic repository, located in Yucca Mountain, Nevada. The NWAP required the nuclear utilities to pay a fee of one mill (0.1 cent) per kWh of electricity generated from nuclear power into the Nuclear Waste Fund, which would be used to finance the construction and operation of the repository. Unfortunately, the radioactive waste repository project has been stalled for decades due to technical, political, and legal challenges, and the federal government has failed to meet its contractual obligation to begin accepting the spent fuel from the utilities by 1998. The fee collection pursuant to the NWAP was suspended by the DOE in 2014, after a court ruling that the fee was not based on a reasonable estimate of the cost of the repository. The Nuclear Waste Fund currently has about $40 billion in accumulated fees and interest, but it is not available for spent fuel management unless Congress appropriates it.

Although the cost of spent fuel storage for nuclear power plants in the US is not reflected in the LCOE of nuclear power plants operations, a study by the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) estimated that the cost of spent fuel storage for nuclear power plants that operate until 2050 would range from another $0.0005 to $0.0015 per kWh (i.e., $0.50 to $1.50 per MWh). Another study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) estimated that the cost of spent fuel management for nuclear power plants in the United States that operate until 2100 would range from $0.0007 to $0.0012 per kWh (i.e., $0.70 to $1.20 per MWh). Both studies were dependent on the availability and timing of a permanent repository or an interim storage facility and the degree of reprocessing and recycling of the spent fuel. However, these estimates are subject to extreme uncertainty and variability, and they do not include inflation adjustments, the potential costs of environmental, health, and security risks associated with spent fuel management, and/or the potential benefits of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution from nuclear power generation, if any.

As previously stated, based on the EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook 2022 (AEO2022), the LCOE for nuclear power, expressed in 2022 dollars per megawatt-hours ($/MWh), is $95.10/MWh (or $0.0951/kWh). Therefore, based on these studies, the on-site cost of management and spent fuel storage for nuclear power plants could add another $0.0006 to $0.0014 per kWh (i.e., $0.60 to $1.40 per MWh) to the LCOE of nuclear power plants. This estimate would increase the LCOE to about $96.50 per MWh.

The current practice and estimated cost associated with spent fuel management and storage in the US is not optimal or sustainable, and there is a need for a long-term solution that is technically sound, economically feasible, environmentally safe, and socially acceptable.

SUMMARY

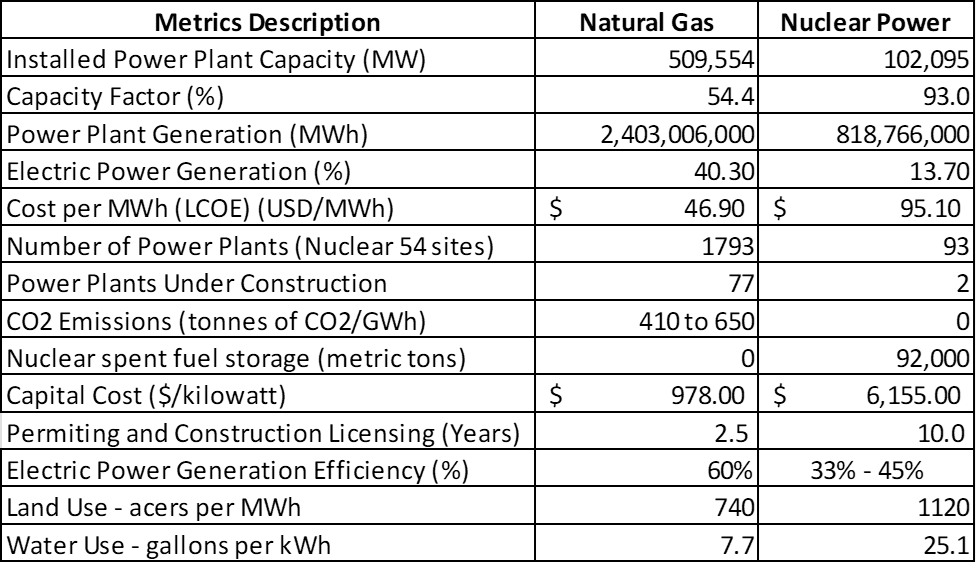

Base on the foregoing the following table summarizes the respective differences between natural gas power and nuclear power.

Table # 1 THE COMPARISON BETWEEN NATURAL GAS & NUCLEAR POWER

Kilowatt (kW) = 1000 watts

Megawatt (MW) = 1,000,000 watts or 1000 kilowatts

Gigawatt (GW) = 1,000,000,000 watts or 1000 megawatts

Kilowatt-hour (kWh) = 1000 watt-hours

US per capita annual electricity consumption = 12,072 kWh/year

CONCLUSIONS

Pursuant to the forgoing metrics between natural gas power and nuclear power, it is clear both electric power sources are supportive, providing reliable and stable base load power to the US power grid. Although both power sources are not going away any time soon, they should be increasing precipitously compared to other less reliable sources of power, such as renewable power sources (wind, solar, hydro, geothermal). However, their future viability is exposed to political biases and deceptive climate change narratives. For the consumer to understand and have the information to weigh-in when discussing the need and trade-offs between natural gas and nuclear power, the table above and the summary below high-light the main points:

- Natural gas is cheaper and more abundant than nuclear fuel, but also emits more greenhouse gases than nuclear power, albeit at far lower levels than other sources such as coal power and even automobiles. Nuclear power is reliable and produces zero CO2 emission, but it faces higher construction and maintenance costs, security risks and safety, which is particularly high regarding spent fuel waste disposal challenges.

- Natural gas is more flexible and responsive to changes in electricity demand, more than nuclear power. Nuclear power can provide a stable and constant base load of electricity but incredibly inflexible regarding startups and shutdowns. However, nuclear power provides stable base load power, which can reduce the need for backup power plants and transmission lines.

- Natural gas is more dependent on fuel market prices and subjected to geopolitical factors, such as climate change narratives that obsess around CO2 emissions, making it more politically volatile and uncertain. Nuclear power is more regulated and carries a high negative public perception regarding safety, which can make it more controversial and politicized.

GLLAHUSEN.COM

January 21, 2024

Leave a comment